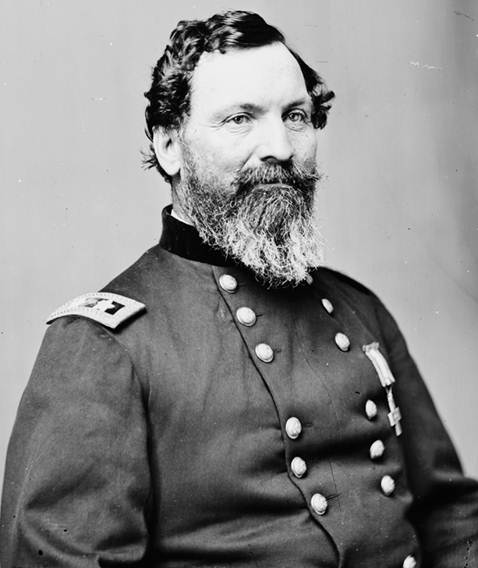

Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick, circa 1864[1]

Early on May 9th, 1864, during the Civil War, Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick was repositioning his brigades and divisions in preparation for the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House in Virginia. He noticed that some of his Union infantrymen were overlapping an artillery position and needed to be redirected. Meanwhile, Confederate soldiers were positioned approximately 500 yards away on a low knoll where artillery and infantrymen were located. The Confederate battalions also included a new contingent of sharpshooters that were armed with a state-of-the-art .451 caliber Whitworth rifle that had an astonishing range of 1,000 yards. As Sedgwick gave orders to his troops, the rebel sharpshooters opened a “sprinkling fire” accompanied by the distinctive whistling sounds of the Whitworth bullets. He chided and shamed his men for dodging the bullets telling them the enemy “couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance.” Moments later, Sedgwick was shot below the left eye and died instantly.[2][3][4]

Sedgwick was the highest-ranking Union officer to die in the Civil War. His career of 27 years began with the Mexican-American War and culminated in the second most deadly battle of the Civil War after Gettysburg. The men under his command affectionately called him “Uncle John” because of his concern for their well-being and his reputation for not sacrificing lives needlessly. During his career he earned so much respect that a shocked Gen. Grant said, “Is he really dead?”

Sedgwick was successful because his experience enabled him to lead through the vagaries of war. Yet, it was that experience that also led him to his fate. He fell victim to the same problem that most of us in business are challenged with – mindsets.

A mindset represents an established attitude or predetermined state of mind. Mindsets are neither good nor bad, right nor wrong. In times of stability, an experienced mindset can lead us through turmoil even when we do not have enough information about the problems at hand. However, in times of rapid change or high uncertainty, mindsets can lead to blind spots, inaction, and incorrect reactions.

We can all think of leaders in history, politics, or business who had mindsets that helped them succeed. However, there are also notable occurrences where the mindsets of experts led to adverse outcomes:

- Irving Fisher was a well-respected economist who helped develop foundational concepts for the profession over his career that began in the 1890s. Renowned economist Milton Friedman called him “the greatest economist the United States has ever produced.” Fisher was also something of a celebrity economist and, in early October 1929, he joined other economists and business leaders in predicting that “stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.” Later that month, of course, the Black Thursday selloff hit, followed by Black Monday and Black Tuesday as the stock market crashed and lost nearly half its value. Fisher remained bullish and called it a temporary slide. By mid-November, he went broke and his sterling reputation was tarnished.[5][6]

- In 1943, Thomas Watson, chairman of IBM said, “I think there is a world market for maybe five computers.”

- “We don’t like their sound, and guitar music is on the way out anyway.” That was the assessment of Dick Rowe, head of Decca Records in rejecting The Beatles after an audition in 1962.

How should we think about our present business environment during a pandemic and global recession? Should management reduce costs, lay off staff, and hunker down to ride out the cycle? Or is this a situation where we will encounter structural change with our markets, clients, and employees. The answer for executive management begins with a challenge to how you think – to understand your mindset.

Characteristics of Mindsets or My “Gut Feel” Is Always Right

Let us start with an understanding of characteristics of mindsets and how they are formed. One of the best examples that I have found is from a book, “The Psychology of Intelligence Analysis” authored by Richards Heuer in 1999 for training analysts for the Central Intelligence Agency.[7] Heuer developed analytical approaches based on the literature of cognitive psychology that he researched from 1978-1986. Though there has been a tremendous volume of work done in cognitive psychology since then, some of the examples he uses are timeless for our purpose in developing business strategy in times of uncertainty.

Heuer discussed the value and the dangers of mental models or mindsets:

[Analysts] construct their own version of “reality” on the basis of information provided by the senses, but this sensory input is mediated by complex mental processes that determine which information is attended to, how it is organized, and the meaning attributed to it. What people perceive, how readily they perceive it, and how they process this information after receiving it are all strongly influenced by past experience, education, cultural values, role requirements, and organizational norms, as well as by the specifics of the information received.[8]

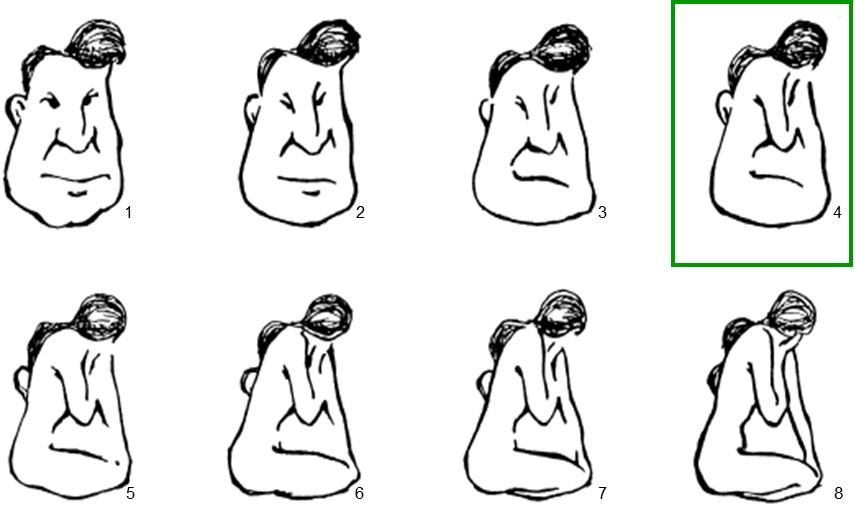

So, how are mindsets formed in our brains? The following sketches from Heuer’s book[9] nicely illustrate key concepts. Begin by viewing the drawing of the man’s face at the top left and move progressively to the lower right sketch. Gradually, the picture changes enough that a drawing of a woman emerges. When these images are isolated and viewed individually, most people do not notice until sketches 6, 7, or 8 that the drawing has changed to a woman. However, objective observers who view the pictures out of sequence would tend to center on sketch 4 as having equal selections for man or woman. When viewed in sequence, it takes observers with anchoring bias[10] much longer to view the change than an objective observer.

This simple yet clever example raises three important points:

- Mindsets are quick to form, but resistant to change.

- New information is assimilated to existing images.

- An unexpected phenomenon requires more information than an expected one.

Understanding these points is critical when assessing the current environment of pandemic, recession, and global uncertainty. Think about how your company viewed the pandemic as it began to unfold. Think about how your company viewed the early warning signs of recession. Finally, think about how your company is anticipating its business outlook.

Neuroeconomics or Why Can’t My Neurons Fire Faster?

Finally, we need to understand a little about the biology of the human brain to shape our understanding of mindsets. Dr. Gregory Berns, a pioneer in the field of neuroeconomics, shared some relevant conclusions in a book titled “Iconoclast: A Neuroscientist Reveals How to Think Differently.” The field of neuroeconomics is focused on how the firing patterns of neurons in the brain govern decision-making and integrate concepts from economics, psychology, and neuroscience. Berns cites the myth that we use 10 to 15% of our brain’s capacity. In fact, the brain has a fixed energy budget of approximately 40 watts (think of a light bulb) and must continually adjust resources to its different areas to function. “The parts of the brain that accomplish their tasks with the least amount of energy carry the moment. Energy is precious; so efficiency reins above all else.” Consequently, the brain takes shortcuts and uses our experiences to develop mindsets.

A good example of mindsets is the mental process that a baseball player undergoes when deciding whether to hit the baseball when at bat. When the ball is pitched, a 90-mph fastball can reach the plate in 0.4 seconds. Since the limit of human reaction time is 0.2 seconds, the batter must decide whether to hit the ball when it is about halfway to the plate. By hitting thousands of balls in training and games, a player develops an automaticity to the swing based on experiential mindsets for myriad conditions relating to the pitcher, the environment, and hitting abilities. The same mindset that allows a batter to hit the ball can also lead business executives and/or leaders to wrong conclusions and poor choices in times of rapid change. Berns took this thought further and said, “The automaticity that provides efficiency can destroy innovation and creativity.” [11]

Lessons Learned

In late June 2020, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) downgraded its global economic growth outlook to a contraction of 4.9% for 2020. As a response to the downturn, governmental fiscal actions have totaled nearly $11 trillion and monetary policy measures represent at least $6 trillion. In the words of the IMF, we are experiencing “a response like no other to a crisis like no other.”[12]

This is truly a situation where our mindsets may not lead us to the best course of action. We need to understand that the mind does not observe reality – it constructs reality. When we form mindsets, they are quick to take shape, but are resistant to change. As we add new information to existing images, we usually do not recognize that our assumptions can be wrong. Finally, it takes more information to recognize an unexpected phenomenon (i.e. a crisis like no other) than an expected one.

There are many ways to challenge your mindsets in a business environment. A large firm with a market research group needs to have training in the wide variety of sophisticated market research techniques that are available. A small firm that typically cannot afford a market research staff needs to provide key personnel with access to multiple industry information sources, diverse viewpoints, and consulting resources. Though the techniques are rich and varied, the bottom line to achieving an objective business outlook is to constantly challenge your own perspective.

If you walk away from this discussion with only one thought, it should be the lesson inherent in the unfortunate death of Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick:

Very few disruptions in business come without warning. They appear to be surprises because people had mindsets that clouded their judgment.

Special thanks to Mark Christopher for copy editing.

Notes

- Gen. John Sedgwick, U.S.A., [Between 1855 and 1864] [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017895765/. ↑

- Cornwall Historical Society. Cornwall and the Civil War: The Death of Sedgwick. http://www.cornwallhistoricalsociety.org/exhibits/civilwar/sedgdeath.html ↑

- Wikipedia. “John Sedgwick.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Sedgwick. ↑

- Ray, Fred. “The Killing of Uncle John” at HistoryNet. June 2006. https://www.historynet.com/the-killing-of-uncle-john.htm. ↑

- Friedman, Milton. Money Mischief: Episodes in Monetary History. United States: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1994, p. 37. ↑

- Latson, Jennifer. “The Worst Stock Tip in History” in Time Magazine Online. September 3, 2014. <https://time.com/3207128/stock-market-high-1929/. ↑

- Heuer, Jr., Richards. Psychology of Intelligence Analysis. CIA Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, 1999. ↑

- Ibid., p. xxi. ↑

- Drawings devised by Gerald Fisher in 1967. ↑

- Many other types of bias are important to this discussion. For brevity, the focus here is on anchoring bias. ↑

- Berns, Gregory. Iconoclast. Harvard Business School Publishing, 2010, pp. 6,7, 15, 16, 35, 36. ↑

- Kanani, Rahim (Editor). “IMF Weekend Read.” International Monetary Fund, 26 June 2020. https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/USIMF/bulletins/2928e7d. ↑