The game of chess is often used as an analogy for strategic thinking in business. The analogy holds up well when a firm plans a series of moves and countermoves. However, in times of rapid change, the thinking process can break down quite severely. We have experienced variability in many drivers of business – but one driver, technology, undergoes transformation at a pace that we cannot anticipate.

The struggle with responding to accelerating technology reminds me of a quote about chess from comedian Dave Barry:

My problem with chess was that all my pieces

wanted to end the game as soon as possible.

Now, it may be that Barry’s struggles with chess were not a function of the pace of the game. Nevertheless, the quote is still a reminder of those firms that did not survive a swiftly transforming world. The pace of change, as a topic for strategic planning, is worth understanding.

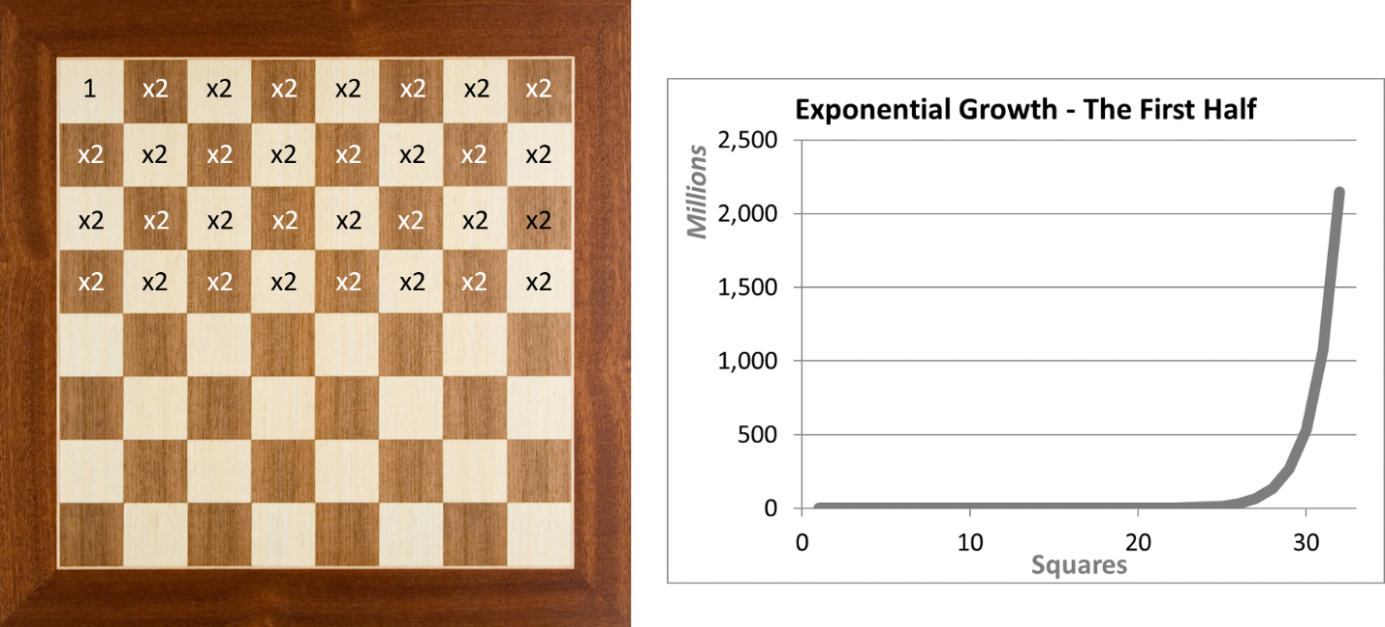

Google’s chief engineer Ray Kurzweil[1], uses the chessboard to tell a story about exponential growth. Kurzweil retells an old tale about when the game was created in India in the sixth century. Chess became so popular with the emperor that he offered the inventor anything he desired. The inventor asked the emperor to place one grain of rice on the first square of a 64-square chessboard. On each succeeding square, he asked the emperor to double the number of grains from the previous square – and continue in likewise fashion across the board.[2]

As shown in the chart, the mathematical implications of the first half of the chessboard are impressive since they result in more than 2 billion grains of rice, which Kurzweil claims would represent a large field of rice. Two billion is a difficult number to grasp but is still a magnitude that we encounter in business.

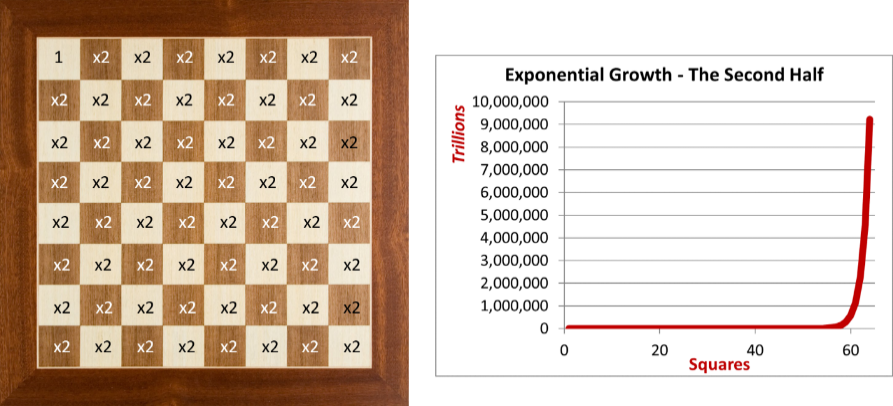

The second half of the chessboard is where the numbers become unimaginable, as shown in the second chart below. One is looking at millions of trillions until the last square is assigned more than 9 quintillion grains of rice – likely more rice than has been cumulatively produced in the history of the world.

The story gives us a perspective for thinking about computing power. The first transistor was built in 1947 by William Shockley, John Bardeen, and Walter Brattain at Bell Labs. By 2017, Intel produced a microprocessor with approximately 8 billion transistors per integrated circuit.[3] Using the chessboard analogy, the exponential growth over the intervening 70 years equates to approximately the 34th square on a chessboard. Consequently, we are already in the second half of a 64-square chessboard.

Furthermore, another tech company, Graphcore, recently produced its GC2 IPU microprocessor that contains 23.6 billion transistors – moving exponentially further in less than two years (a couple more squares ahead on the board).

The accelerating rate of change in computing technology is now being matched by advances in artificial intelligence (AI). Let’s turn back to the chessboard to summarize the phenomenon. Programmers amazed the world in the 1990s when they worked with top chess players to program the logic for the game of chess. The ultimate accomplishment occurred when IBM’s Deep Blue computer defeated then-world champion Gary Kasparov in 1997.

Now, as part of the second half of the chessboard, Google’s advanced development company, DeepMind[4], created the AI software AlphaZero for the game of chess. What is different now is that the DeepMind engineers taught AlphaZero only the rules and did not program complicated chess algorithms with banks of opening moves. Instead, AlphaZero had to teach itself how to play by conducting 44 million ultra-fast games. In eight hours, it taught itself to be at the superhuman level of play. In December 2018, DeepMind released 210 games of a match in which AlphaZero beat Stockfish 8 (then the strongest chess-playing computer in the world) with 155 wins and six losses.

As amazing as the chess example is, even more astounding is the real goal of DeepMind in developing AlphaZero. It demonstrated the power of an artificial intelligence algorithm that could achieve a superhuman level of performance through self-training with minimal human input.[5]

Many futurists, notably Kurzweil, have studied the accelerating rate of technological change and the evolutionary growth of resulting products. Not too long ago, Kurzweil said, “We won’t experience 100 years of progress in the 21st century—it will be more like 20,000 years of progress (at today’s rate).[6]

So, what does the second half of the chessboard mean? It means that just when we were getting used to email and the internet – cell phones came along. Just as we were getting used to flip phones, smart phones came along, then tablets, then robotics, then drones, and now artificial intelligence. AI is, in turn, developing so quickly and affecting so many parts of our world that forecasting becomes difficult (see my previous post on “Peak Horses to Peak Autos”[7]).

The crux of the matter is crystallized by someone who is renown in fields of endeavor other than technology – Henry Kissinger. Last summer, Kissinger authored an article in The Atlantic entitled “How the Enlightenment Ends: Philosophically, intellectually—in every way—human society is unprepared for the rise of artificial intelligence.”[8] In the article, the former secretary of state contrasts the rapid advancement of AI with the historical period of the Age Enlightenment in the 18th century. The Age of Enlightenment (or the Age of Reason) was represented by the sweep of philosophical ideas that were spread by technology (the printing press).

Now we are faced with the opposite situation – the technology that is exponentially advancing is seeking a guiding philosophy. Our soul-searching question is “How will society respond to this challenge?”

As always, your thoughts and ideas are welcome.

Notes:

- Ray Kurzweil is also a renowned futurist, inventor, and author. This story is recited in his book The Age of Spiritual Machines: When Computers Exceed Human Intelligence, 2000, p. 36. ↑

- The story is retold in The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies by Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee (2014, p. 45). ↑

- 28-core Xeon Platinum 8180 microprocessor ↑

- DeepMind is an AI company in London that was acquired by Google’s parent company Alphabet in 2014. See https://deepmind.com/blog/article/alphazero-shedding-new-light-grand-games-chess-shogi-and-go ↑

- Sadler, Matthew and Natasha Regan, “The chess computer which could shape our future” in The Scotsman. 19 August 2019. ↑

- Kurzweil, Ray. Quote listed on the Singularity University’s website, https://su.org/resources/exponential-guides/the-exponential-guide-to-the-future-of-learning/ ↑

- https://sebestaconsulting.com/2019/09/peak-horses ↑

- The Atlantic Magazine. June 2018 issue, <https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/06/henry-kissinger-ai-could-mean-the-end-of-human-history/559124/> ↑