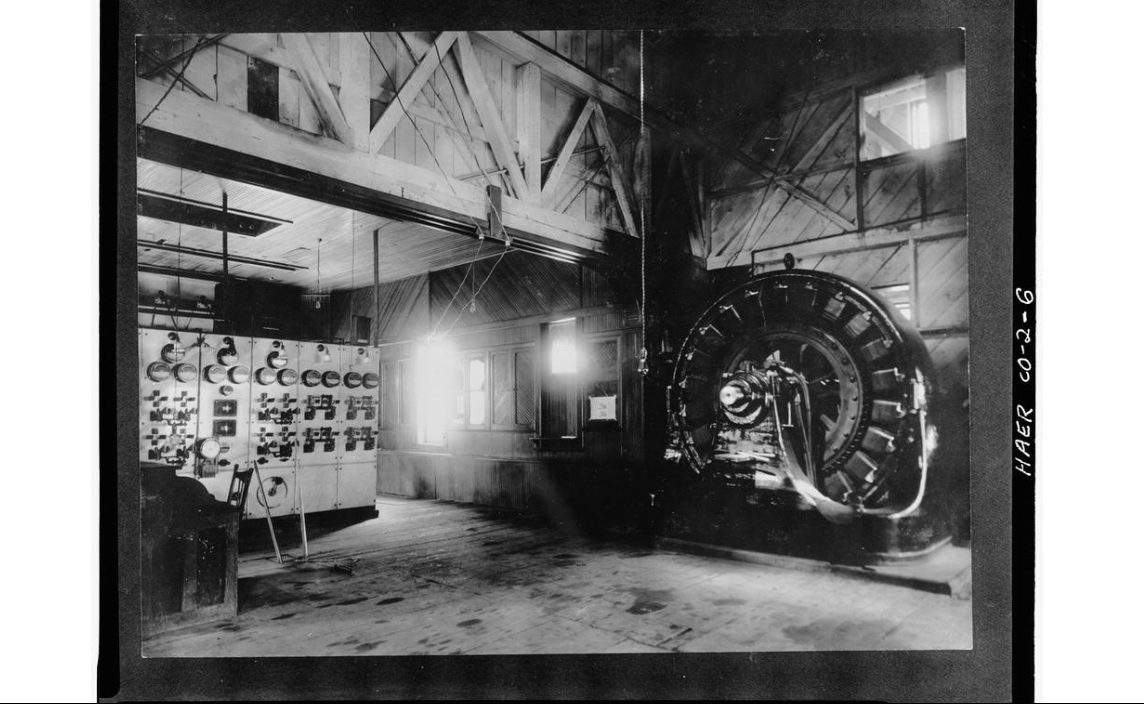

Ames Hydroelectric Plant Powerhouse, circa 1895[1]

There is a myth that the construction industry is slow to adopt new technology.[2] We were just getting used to spreadsheets when email and the internet came along. Now we have emerging applications for robotics, drones, and even artificial intelligence (AI). Underpinning all these trends (especially AI) are sweeping advancements in computing power, which will continue its exponential growth. In December 2020, a team in China announced it had demonstrated a “quantum advantage” computation taking just 200 seconds to complete – a process that would require 2.5 billion years for a classical supercomputer to replicate.[3] Meanwhile, as we experience head-spinning technological changes all around us, the construction industry appears to plod along with established practices. A quick look at history shows that this is not the case.

In the 1870s, major advances in electricity generation spurred the development of electric lighting. By 1880, Thomas Edison patented the incandescent electric light bulb and two years later built the first direct current central power station in New York City.[4] Then, in 1890, Lucien Nunn, a restaurateur-turned-carpenter and lawyer-turned-journalist, became a gold miner and found a new application for electricity at a 12,000-foot elevation in a gold mining region in southwestern Colorado.[5] Other mines burned most of the nearby timber as fuel for steam engines to power their mining operations. Consequently, the denuded forests left a decreased timber supply and fuel became expensive. Nunn found a new technology supplied by George Westinghouse that could produce electricity with alternating current (AC) from a hydroelectric plant. He built the plant on the south fork of the San Miguel River at an 8,700-foot elevation and then sent the electricity 2.6 miles up the mountain on a transmission line to the stamp mill and mine. The Ames Hydroelectric Generating Plant near Telluride, Colorado, became the world’s first AC plant in June 1891.[6] The plant, owned by Xcel Energy, is still in operation.

Projects such as the Ames hydro plant represented the culmination of multiple developments across various disciplines and industries. Inventiveness, competition, engineering, manufacturing innovation, and novel approaches to construction all combined to push the technology frontier. As these ventures coalesced and moved in the same direction, the technology momentum led to new enterprises: plants to manufacture equipment for electricity generation and transmission; utilities to sell and distribute power; professional societies to develop codes and standards; engineering and construction firms to keep up with the demand. Other industries evolved to supply fuel for electric power and to provide applications that use electricity to improve everyday life. These major sectors of the current U.S. economy are supported by a construction industry composed of more than 800,000 firms employing more than 7 million people – accounting for approximately 4.2% of the nation’s GDP.[7]

In some ways we are in a similar period as the late 1800s, characterized by rapid technological developments along many paths, at different rates, in varied industries. Technology in the construction industry (according to the Construction Industry Institute) broadly refers to “the collection of innovative tools, machinery, modifications, software, etc. used during the construction phase of a project that enables advancement in field construction methods, including semi-automated and automated construction equipment.” The key question for business in the long run is how these disparate advancements will come together to on behalf of industrial progress.

Over the next ten years, we will see a new era of construction as technology continues to revolutionize industries. For early stage applications, we are already seeing modular hospitals, houses and buildings built in a matter of days; replacement parts and even small structures “printed” with additive manufacturing techniques; autonomous bulldozers and excavators; survey drones; 3-D lasers that can scan existing facilities; 5-D building information modeling (BIM); robots that lay bricks and tie rebar; applications for virtual and augmented reality; fiber-reinforced polymers instead of traditional concrete and steel; self-healing concrete; artificial intelligence algorithms to monitor structural stress with thermal imagery; cloud-based platforms to integrate communication between the office and sites; and much more. The scale of these innovations builds momentum for adopting technology that will transform existing industries and create new ones.

So how does a construction firm evaluate this wave of change? The first step is to develop a course of action that focuses on engineering, construction, and operations. This should include an evaluation of three key factors: (1) ownership, (2) alliance with vendors and manufacturers, and (3) positioning as technology neutral. The first two require strategic timing and business positioning; neutral positioning, the most common approach, requires close working relationships with technology providers.

Finally, a firm needs to focus on how to integrate technology into strategy. It must invest resources in key personnel, equipment, operations, and maintenance so that it is continually aware of ongoing developments. Firms need to fully understand the factors that are driving technology in their business and to assess the proper timing for investment. The greatest business risk is that your competitors will rapidly bypass your importance to the industry.

When Google conducted an extensive expansion of its services and then experienced cascading failovers of its email system in 2011, its vice president of engineering, Urs Hölzle, warned that “at scale, everything breaks.” He was referring to the tradeoff between complexity and massively scaled email services. However, he was not thinking of construction – construction is “technology at scale.” The applications are imposing not only for data and software, but also for materials, equipment, earthmoving, and personnel. As we have seen from history, the momentum of technology in construction will shape current industries and spur new ones.

Special thanks to Mark Christopher for copy editing.

Notes

- Photograph Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/co0030/. ↑

- Originally published in xplorexiT, March 5, 2021, https://xplorexit.com/new-era-construction-will-drive-industries-innovate/. ↑

- Ball, Philip. “Physicists in China challenge Google’s ‘quantum advantage,’” in Nature. Vol 588, p. 380, 3 December 2020. ↑

- Pearl Street Station from the Engineering and Technology History Wiki (ETHW), https://ethw.org/Pearl_Street_Station. ↑

- Switzer, Caitlin. “Let There Be Light…L.L. Nunn and the Ames Power Plant” in The Montrose Mirror, January 16, 2013, http://montrosemirror.com/uncategorized/let-there-be-light-l-l-nunn-and-the-ames-power-plant/. ↑

- Hughes, Alfred and Richard Rudolph. “Ames Hydro: Making History Since 1891” in Hydro Review, Issue 7 and Volume 32, August 27, 2013, https://www.hydroreview.com/2013/08/27/ames-hydro-making-history-since-1891/#gref. ↑

- The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. ↑