In the early days of the automobile, a great uncle of mine worked for Harvey Firestone to develop the pneumatic tire. He stood on the running board with a pistol and shot the tire to test the performance during a blowout. These were heady days of new technologies, emerging business models, and intense competition. These were also the days when horse transportation was so well-established that people had trouble envisioning something new until, suddenly, that something new was all around them on the streets.

Today, we occasionally hear about autonomous (self-driving) vehicles, electric vehicles, and ridesharing on the news. In the past couple of years, even business people have grown accustomed to ridesharing services, such as Uber and Lyft. Most of us have, at least, heard of someone who owns a hybrid or electric vehicle. However, these transportation options are far from the mainstream. How can we see clearly what may become common and what may not?

The Early Days and Peak Horses

Before the early 1900s, the automobile was thought of as a novelty. The world’s first speeding ticket reportedly occurred on January 28, 1896 in Paddock Wood, Kent, England. Walter Arnold sped past a bobby at the breakneck speed of 8 mph – 6 mph over the speed limit. To further flout the system, he did not have a man with a red flag preceding him, as required by law. He was charged with several counts, including operating a “locomotive without a horse” – or a horseless carriage.[1]

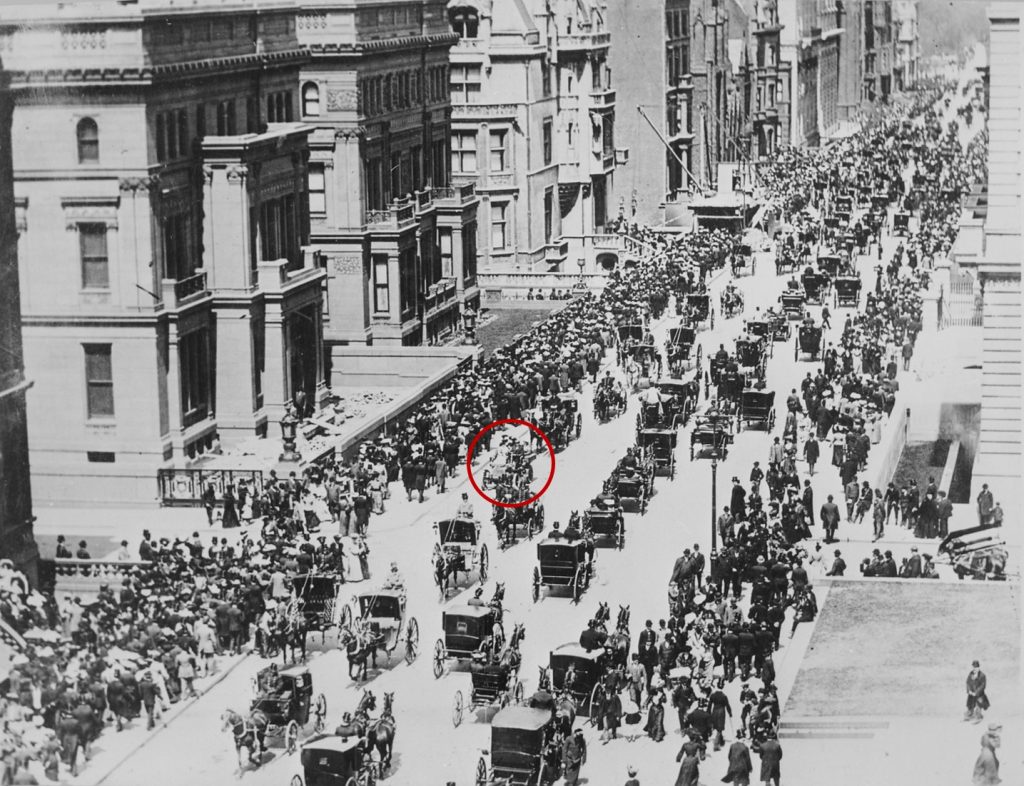

In the early 1900s, horses were the transportation mode of the cities. New York City, which had the largest population in the country, reportedly had a horse population of 100,000. In addition to worsening urban congestion, the large number of horses created environmental problems – about 2.5 million pounds of manure per day.[2] This was a time when the novelty of automobiles was just barely starting to show in the cities.

As the early 1900s progressed, the horseless carriage technology began to take off. According to the census of 1900, there were 4,192 vehicles produced in the United States, and these were powered by the following technologies:

- 22% gasoline

- 38% electric

- 40% steam

By 1914, the technology had evolved to the internal combustion engine. Ninety-nine percent of the 568,000 automobiles produced at that time had an internal combustion engine.[3]

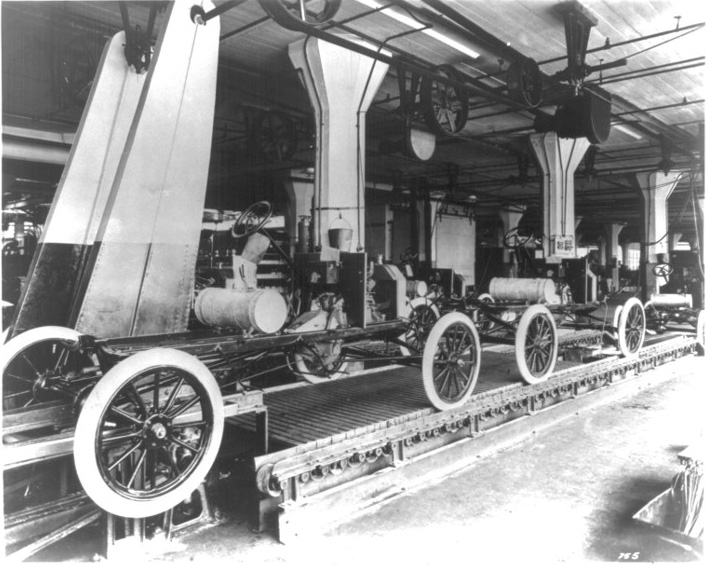

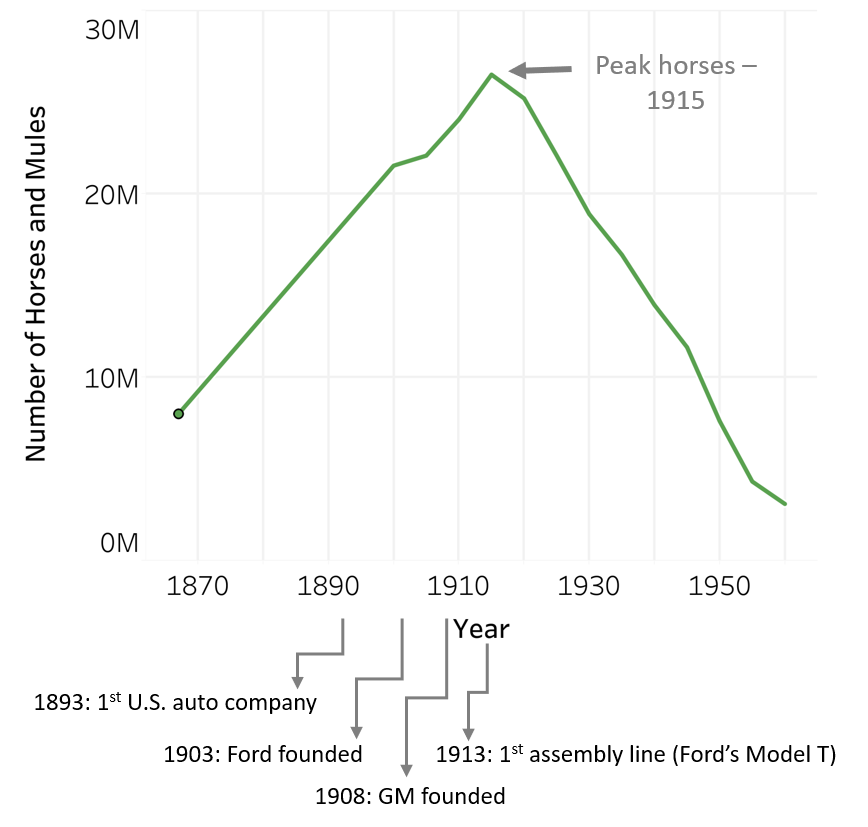

Not only was the technology evolving, but so were diverse business models. The first U.S. auto company began operations in 1893. Ford was founded in 1903, followed by GM in 1908. In New York City alone, fifty automotive manufacturing companies opened between 1900 and 1920.[4] This was the heyday of automotive development. The contrasting photos of New York City in 1900 and 1913 capture the stark difference in modes of transportation.

During this time period, the horse population experienced a sea change. As automobile production ramped up for the next 100+ years, the horse population began to decline rapidly, especially in the cities. Ultimately, the number of horses in the country peaked around the year 1915 (see the chart).

Peak Autos?

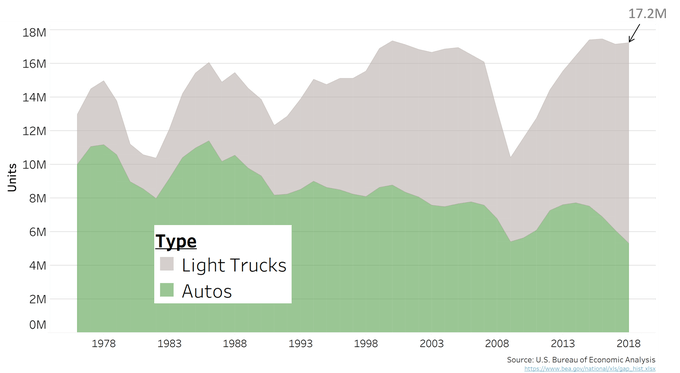

Meanwhile, automobile production continued to ramp up until the 1980s (the green area in the chart below). Even coming out of the depths of the Great Recession in 2009, auto sales recovered some and then declined to 5.3 million autos – slightly below 2009 levels.

Sales of light trucks increased rapidly after the Great Recession and offset much of the decline in auto sales. Total light vehicle sales, including light trucks, reached a peak of 17.5 million in the year 2016. Sales fell slightly in 2017 and 2018.

Two big questions that the automotive industry in the United States is wrestling with are:

Have we reached peak autos?

Have we reached peak vehicles?

The answers are unclear because we are in the middle of several rapidly changing, and potentially conflicting trends.

- Congestion and gridlock continue to increase in major cities. Autonomous vehicles will reduce congestion through ridesharing and robotaxis. However, a key uncertainty is how many people who do not drive, or those drivers who own standard cars, will purchase autonomous vehicles, and consequently increase congestion.

- Young people are delaying the age when they obtain their driver’s license. In 1983, 46% of 16-year old teens had their license; in 2014, only 24% had their license.[6]

- Consumer preferences are changing as demonstrated by the growth of ridesharing services such as Uber and Lyft.

- Electric-vehicle technology requires a massive build-out of car-charging networks. GM, Tesla, and Volkswagen have major programs under way – but the infrastructure needs to be added across the country.

How should we analyze the future? One way is to look at industry perspectives to see how companies are changing their business models.

New Business Models

The executive chairman of Ford Motor Company, William Clay Ford, Jr. has said that everything about the business model is being disrupted, from ownership to propulsion to the need for a driver. On the demand side, he said that mobility is the true goal now. He quoted his great grandfather, Henry Ford, as saying

“If I asked my customers at the time what they wanted,

they would have said ‘a faster horse.’”[7]

The demand for passenger vehicles has been declining enough that Ford Motor announced last year that it is planning to discontinue production of nearly all passenger cars in North America – except the Mustang. Meanwhile, Ford is working on electrifying its best-selling vehicle in the U.S., the F-150 pickup truck. The company also acquired a firm in Pittsburgh, ARGO, which is one of the leaders in autonomous vehicles. They are rapidly working to catch up to other companies that are quickly changing business models (especially the tech firms).

Companies are moving in different strategic directions. GM and Volkswagen recently announced that they are moving away from producing hybrids to focus on fully electric cars. GM is developing 20 fully electric models across the world over the next four years. Volkswagen is planning to use expansion of operations in China to develop economies of scale in electric car production. Other companies, such as Toyota and Ford, are maintaining their current approach to keep producing (and in some cases, expanding) their hybrid models.[8]

There is a scramble for the right ownership model. On the one hand, there are OEMs (original equipment manufacturers), such as Ford and GM, that are rapidly trying to get up to speed on the technology and software by acquiring tech firms to continue as a vertically integrated supplier of vehicles. On the other hand, there are tech companies that are either building their own manufacturing plants (e.g., Tesla) or are forming consortiums to compete with the OEMs (e.g., Google, Lyft, and Uber). There is even an auto parts supply company, Aptiv, formerly Delphi, that is testing autonomous vehicles.

Analyzing the future requires answering key questions, not the least of which will revolve around regulatory and legal battles, infrastructure investment, human psychology, consumer preferences, and the effectiveness of cyber security. The ramifications beyond vehicle sales can potentially be far-reaching by disrupting supply chains, car insurance, vehicle financing, service stations, and even real estate (urban parking lots).

As we enter a resurgent heyday for the industry, the ultimate question for emerging business models is:

Sell cars or sell mobility as a service?

Stay tuned for my next post in two weeks “The Silver Lining in Strategic Planning.”

Notes

- Bibby, Miriam. “Walter Arnold and the World’s First Ever Speeding Ticket.” Historic UK. (March 19, 2019). https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Walter-Arnold-Worlds-First-Speeding-Ticket/ ↑

- Johnson, Ben. “The great Horse Manure Crisis of 1894.” Historic UK. https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Great-Horse-Manure-Crisis-of-1894/ ↑

- Hiskey, Daven. “In 1899, Ninety Percent Of New York City’s Taxi Cabs Were Electric Vehicles.” Today I Found Out, Feed Your Brain. (April 28, 2011). http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2011/04/in-1899-ninety-percent-of-new-york-citys-taxi-cabs-were-electric-vehicles/ ↑

- Barron, James. “Cars and the City, Imperfect Together.” The New York Times. (March 19, 2010). ↑

- Data extrapolated from multiple sources: Ensminger (1969), cited in Kilby, Emily R. “The Demographics of the U.S. Equine Population.”; Equine Heritage Institute, http://www.equineheritageinstitute.org/learning-center/horse-facts/ ; and Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horses_in_the_United_States. ↑

- Sivak, Michael and Brandon Schoettle. Recent decreases in the Proportion of Persons with a Driver’s License across All Age Group. University of Michigan. (January 2016). And Beck, Julie. “The Decline of the Driver’s License.” The Atlantic. (Jan 22, 2016). ↑

- William Clay Ford, Jr. is also the great-grandson of Henry Ford. He spoke at the CERAWeek Conference in Houston (March 12-15, 2019). ↑

- Colias, Mike. “GM, Volkswagen Say Goodbye to Hybrid Vehicles: Toyota, Ford plan to keep hybrids as core part of their lineups, showing split in auto industry,” in The Wall Street Journal, August 12, 2019. https://www.wsj.com/articles/gm-volkswagen-say-goodbye-to-hybrid-vehicles-11565602200?mod=hp_lead_pos5

Another interesting (and a bit older) article about peak horses, peak cars, and GM’s evolving business model: Tetzeli, Rick. “GM gets Ready for a Post-car Future.” Fortune Magazine. (May 8, 2018).

https://fortune.com/2018/05/23/gm-general-motors-fortune-500/ ↑